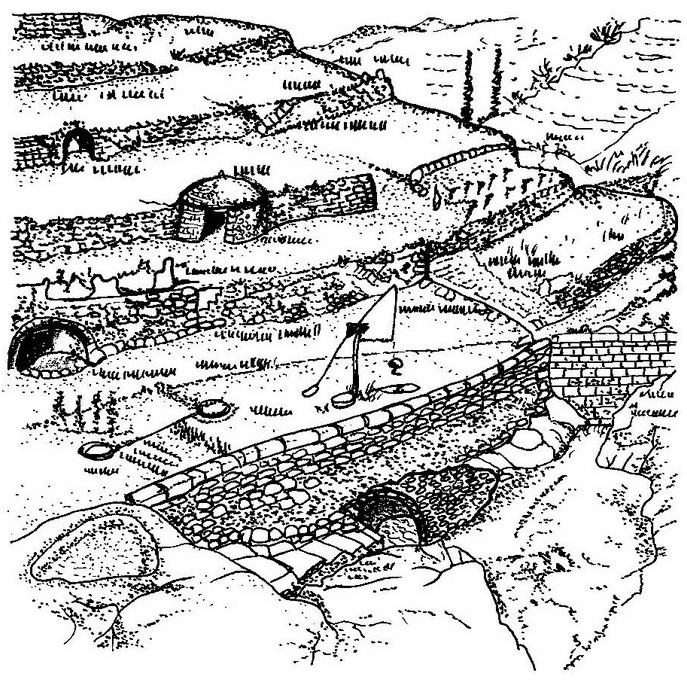

Già nella fase di sedentarizzazione senza agricoltura, vengono realizzate strutture di contenimento del suolo con muri di sostegno e ambienti impermeabilizzati.

Nelle zone aride dell’Africa e del Medioriente, nascono modi originari di coltivazione che sfruttano le poche risorse a disposizione e creano dispositivi per la cattura dell’acqua.

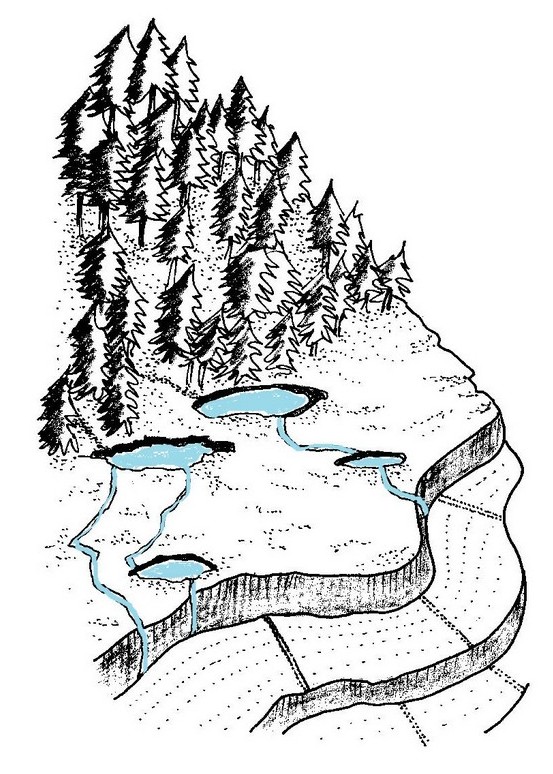

In aree che presentano condizioni di alternanza climatica, si realizzano perimetri di fossati scavati nella roccia che hanno funzioni polivalenti, come il drenaggio dell’acqua, la raccolta dei liquami e dei rifiuti, molto utili per la concimazione dei suoli.

Inoltre, queste realizzazioni,sono risultate fondamentali per l’individuazione del periodo della semina delle diverse specie di piante che, all’interno dei fossati, germinavano spontaneamente.

Durante l’Età dei Metalli, con l’uso di carri e cavalli, cambiano le tecniche di sfruttamento dei terreni agricoli.

Gruppi organizzati agro-pastorali, si spostano dalle zone montane verso il mare, in una sorta di transumanza.

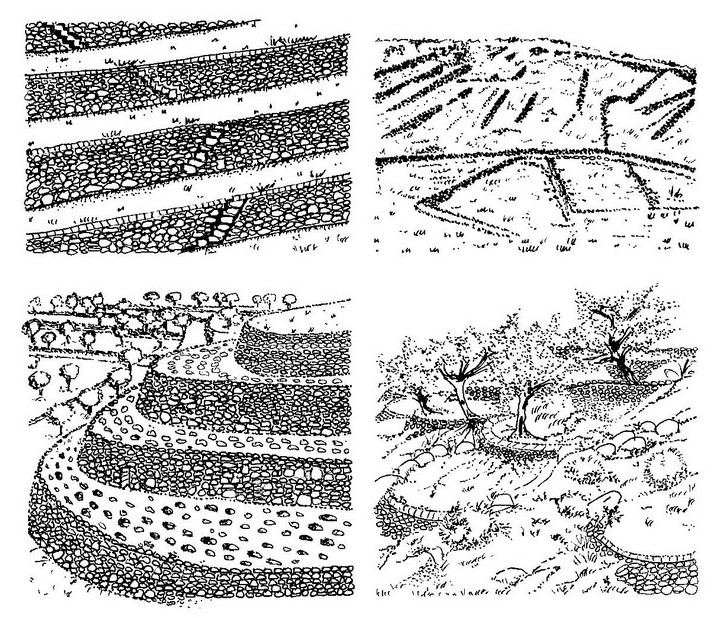

Dove le impervie pendenze del terreno non permettono la coltivazione del suolo, si realizzano i terrazzamenti e nei bacini interfluviali,si creano giardini pensili.

Il terrazzamento protegge il pendio, ricostituisce il suolo, raccoglie acqua, marca lo spazio ed ha un’ alto valore estetico.

Inoltre, è molto importante, a livello paesaggistico, per le zone collinari ed i pendii presenti in tutto il bacino del Mediterraneo ed in Europa.

L’uso, a grande scala, della tecnica dei terrazzamenti, si rivelerà un ingegnoso sistema di edificazione dello spazio, un metodo fondamentale di organizzazione del paesaggio.

I pendii terrazzati con i muri a secco, i drenaggi, le prese d’acqua, sono tecniche che si tramandano, nel tempo, all’interno della società e vengono applicate, su grande scala, in tutto il mondo.

Already in the phase without sedentary agriculture, they are made of soil containment structures with supporting walls and sealed environments. In arid areas of Africa and the Middle East, born original ways of cultivation that take advantage of the few resources available and create devices for water capture. In areas with alternation of climate conditions, it is made of perimeter ditches dug in the rock having multipurpose functions such as water drainage, sewage collection and waste, very useful for fertilizing soil.

In addition, these works have been vital for the identification of the period of the sowing of different species of plants, inside ditches, spronted spontaneously. During the Age of Metals, with the use of chariots and horses, they change the exploitative techniques of agricultural land.

Organized groups agro-pastoral, moving from the mountainous areas to the sea, in a kind of transhumance. Where the steep gradients of the terrain does not allow the cultivation of the soil, they realize the terraces and in interfluvial basins, creating hanging gardens.

Terracing the slope protects, replenishes the soil, water collects, brand space ared has a high aesthetic value. Moreover, it is very important, in landscaping, for hilly areas and slopes located, throughout the Mediterranean basin and Europe. The use, on a large scale, the technique of the terraces, will prove an ingenious space of building system, a fundamental method of landscape organization.

The terraced slopes with dry stone walls, drains, water intakes, are techniques that have been handed down over time, within the company and are applied on a large scale around the world.

Yuan Yang (Cina)

Terrazzamenti

Quando il terreno ha una pendenza tale da rendere difficoltose le operazioni di coltivazione delle colture (erbacee e arboree), si usa il sistema a terrazze.

Con questo metodo, diminuisce la pendenza e si realizzano muri che sostengono il terreno accumulato per spianare le superfici da coltivare.

I terrazzi hanno funzioni diverse come : il controllo e la gestione idraulica per l’incanalamento delle acque pluviali, lo smaltimento delle acque in eccesso e l’irrigazione.

Diminuendo la pendenza del terreno, viene rallentata l’erosione del pendio in caso di precipitazioni eccessive.

Con questo sistema si forma e si mantiene un substrato coltivabile che sarebbe impedito dalle forti pendenze.

Il suolo mantiene una certa umidità e si crea, inoltre, un microclima favorevole alle radici, garantito dal calore immagazzinato dalle pietre porose che facilitano la maturazione delle colture.

Terracing

When the land has a slope that difficulties in the operations of cultivation of crops (herbaceuous and woody), the system is used on terraces. With this method, the slope decreases and are realized walls that support the soil accumulated to smooth the surfaces to be cultivated. The terraces have different functions such as : the control and the hydraulic management for the channeling of rain water, the disposal of excess water and irrigation.

Decreasing the slope of the terrain, the slope erosion is slowed down in the event of excessive rainfall. With this system is formed and maintains a tillable substrate that would be prevent by the steep slopes. The soil retains some moisture, and it also creates a microclimate favorable to the roots, guaranteed by the heat stored by the porous stones that facilitate the maturation of crops.

Oliveti – Capriglia e Valdicastello (Toscana)

Un tipico sistema di terrazzamenti in pietra, usato sulle colline toscane, per la coltivazione degli olivi.

Olive groves-Capriglia and Valdicastello(Tuscany)

A typical stone terracing system used in the Tuscany hills, for the cultivation of olive trees.

Capriglia (Toscana) Terrazze coltivate a olivi

Terrazzamenti a Valdicastello (Toscana)

Terrazzamento – Capriglia (Toscana)

La mancanza di manutenzione dei terrazzi, determina una situazione di degrado del pendio che, con le piogge abbondanti, provoca l’erosione del terreno.

Terrace – Capriglia (Tuscany)

The lack of mantenance of terraces, determines a slope degradation situation, with abundant rainfall, causing soil erosion.

Degrado del terrazzamento per la mancanza di manutenzione

Gradoni nel Sasso Barisano a Matera (Basilicata)

Stepped in Sasso Barisano to Matera (Basilicata)

The steps of the slope below the Sant’Agostino church testify to the plot matrix terraces, artificially made with retaining walles.

Nel Sasso Barisano i gradoni sul pendio sottostante la chiesa di S.Agostino testimoniano la trama matrice a terrazzi, artificialmente realizzati con muri di sostegno

Zocos a Lanzarote (Spagna)

Vigneti nella zona di Geria. Le piante sono protette da zocos, mezzalune in pietra lavica che trattengono l’umidità e funzionano come collettori di rugiada.

Le piante crescono in mancanza assoluta di sorgenti e falde.

Zocos to Lanzarote (Spain)

Vineyards in the Geria area. The plants are protected by zocos, crescents in lava stone that retain moisture and work as the dew collectors. The plants grow in absolute lack of springs and aquifers.

Isola di Lanzarote (Spagna) Mezzalune di pietra lavica chiamate zocos

Terrazze alle Cinque Terre (Liguria)

Pendii a strapiombo sul mare coltivati a vigneti con la tradizionale tecnica dei terrazzamenti liguri.

Questo delicato ecosistema necessita di un’accurata e costante manutenzione delle terrazze affinchè non si verifichino situazioni di forte degrado ambientale che ha causato ingenti danni in passato.

Terraces to Cinque Terre (Liguria)

Slopes overlooking the sea of vineyards with the traditional tecnique of the Ligurian terraces. This delicate ecosystem requires careful and constant maintenance of the terraces so that there will be no strong environmental degradation that caused extensive demage in the past.

Cinque Terre (Liguria) Vigneti terrazzati sul mare

Cinque Terre (Liguria) Un terrazzamento nella parte interna sulle colline delle Cinque Terre

Cinque Terre (Liguria) Particolare di un terrazzamento

Cinque Terre (Liguria) Panorama con vigneti terrazzati

Cinque Terre (Liguria) Un ampio vigneto terrazzato a strabiombo sul mare

Particolare del carrello per il trasporto dell’uva

Cinque Terre (Liguria ) Vigneti a picco sul mare

Cinque Terre (Liguria) Ampi vigneti terrazzati

Cinque Terre (Liguria) Particolare di un terrazzamento a Corniglia

Cinque Terre (Liguria) Particolare di un terrazzamento verso Manarola

Monte Marcello – Particolare di terrazzamento in pietra

Terrazzamenti (Yemen)

Gli altipiani yemeniti, sono scolpiti da estensioni di terrazzamenti in pietra coltivati.

Questa tecnica è molto diffusa nel territorio ed è alla base dell’organizzazione del paesaggio di tutto lo Yemen.

Terraces (Yemen)

Yemeni highlands, are carved from stone terraces cultivated extensions. This technique is very widespread in the territory and is the basis of the organization of all Yemen landscape.

Yemen del nord – Altipiani terrazzati

I muretti a secco chiamati marbid raccolgono l’umidità prodotta sulle superfici piane intorno.

The dry stone walls called ” marbid” collect the moisture produced on the flat surfaces around.

Yemen del nord – Coltivazioni nel wadi Gazwa

Negli avvallamenti degli wadi,si coltivano ortaggi con il sistema dei terrazzamenti in pietra.

In the valleys of the wadi, vegetables are grown with the stone terracing system.

Yemen del nord – Coltivazioni a terrazze nel fondo del wadi

Al di sotto dell’acropoli di Thula, nel nord dello Yemen, il paesaggio è scandito da terrazze coltivate alternate a recinti di terra cruda e cisterne per la raccolta di acqua piovana, utilizzata anche per le colture.

Below the Acropolis of Thula, in northern Yemen, the landscape is punctuated by alternating cultivated terraces in the enclosure of raw land and cisterns to collect rain water, also used for crops.

Thula (Yemen del nord) Terrazzamenti sotto l’acropoli della città

Shaharah (Yemen del nord) – Ad un’altezza di circa 3000 metri, raggiungibile mediante una piccola strada sterrata considerata tra le più rischiose al mondo, si trova la città di Shaharah situata all’estremo nord dello Yemen.

I suoi suggestivi terrazzamenti in pietra, si sviluppano sui ripidi pendii a strabiombo sulle gole rocciose.

Shaharah (North Yemen) – At a height of about 3000 meters, accessible by a small dirt road considered among the most dangerous in the world, it is located the city of Shaharah situated in the far north of Yemen.

Its picturesque stone terraces, grow on the steep slopes to overhang the rocky gorges.

Shaharah (Yemen del nord) Terrazzamenti sui ripidi pendii montani

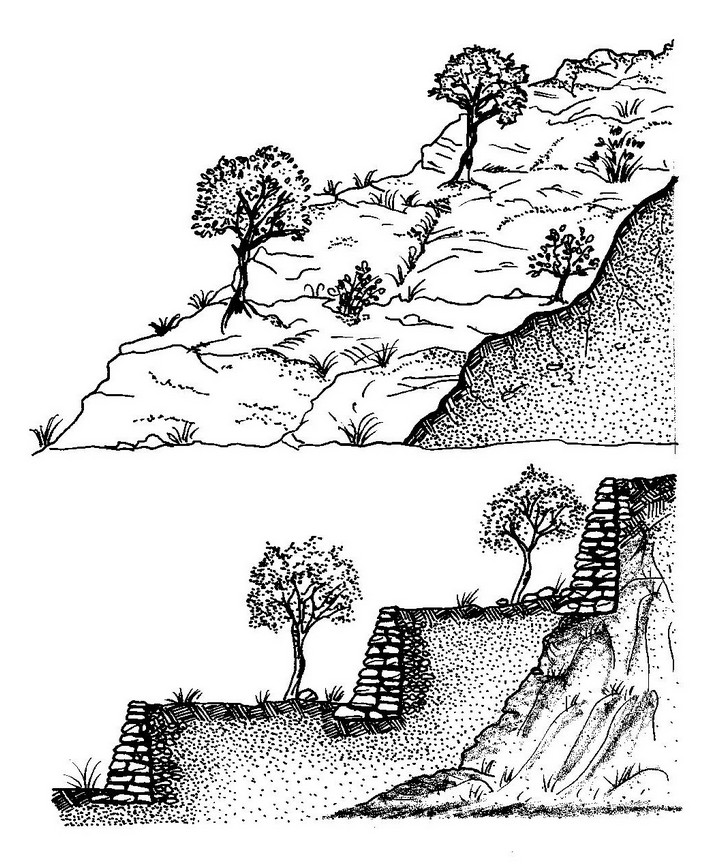

Schemi-Tipi di terrazzamenti nella zona di Mallorca (Spagna)

La realizzazione di un terrazzamento viene effettuata con la costruzione di un muro a secco più alto del profilo del terreno, a valle del terrazzamento da realizzare.

Si effettua l’escavazione e riporto della terra a riempimento dello spazio tra muro e roccia, in modo da formare una superficie pianeggiante.

Viene costruito, poi, un nuovo muro a secco a monte del terrazzo realizzato.

Schemes-Types of terraces in the area of Mallorca (Spain)

The realization of a terracing is carried out with the construction of a higher dry wall of the soil profile, to the terracing valley to realize. It carries out the excavation and filling of the earth to file the space between the wall and the rock, so as to form a flat surface. Is constructed, then, a new dry wall upstream of realized terrace.

Schema della costruzione di un terrazzamento

Terrazzamenti a Mallorca (Spagna)

Schema di terrazzamento ( modificato da disegno di Ambroise 1989)

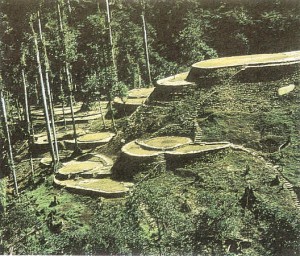

Zabo (India)

Il sistema Zabo, era praticato in Nagaland nel nord-est dell’India.

Associava la conservazione dell’acqua con la silvicoltura e l’agricoltura e cura del bestiame.

I villaggi dove esistono ancora gli zabo, sono situati su di un alto crinale in aree altamente piovose.

La pioggia cade sopra una macchia di foresta tropicale, situata sulla cima della collina e scorre giù per il pendio attraversando vari piani di terrazze.

L’acqua viene raccolta in pozze situate sui piani dei terrazzamenti dove pascola il bestiame.

Mediante piccole canalizzazioni, raggiunge la zona delle risaie situate ai piedi della collina.

Zabo (India)

The Zabo system was practiced in Nagaland in northeast of India. Water conservation associated with forestry and agriculture and livestock care.

The villages where there are still the Zabo, are located on a ridge in high rainfall areas. The rain falls over a tropical forest vegetation, located on the hill top and flows down the slope through various lovels of terraces. The water is collected in pools located on the floors of terraces where the livestock graze. Through small ducts, it reaches the area of rice fields located at the foot of the hill.

Ricostruzione del sistema Zabo

Grandi terrazzamenti (Yemen)

SISTEMA AGRICOLO SABEO E NABATEO

– I bassi muri di pietra a secco chiamati marbid, organizzano la pendenza delle terrazze e raccolgono l’umidità prodotta sulle superfici piane.

Large terraces (Yemen)

AGRICULTURAL SYSTEM SABAEAN AND NABATAEAN

Low dry stone walls called ”marbid”, organize the slope of the terraces and collect the moisture produced on flat surfaces.

Wady Gazwa, Yemen del Nord – Particolare di terrazzamenti con il sistema marbid

I muri di pietra e le dighe chiamate harrah, condividono le quote d’acqua che assicurano, alle larghe terrazze, l’umidità necessaria alle coltivazioni.

The stone walls and dams called ”harrah” which share out the water quotas that ensure, to the wide terraces, the necessary moisture for crops.

Yemen del nord – Particolare delle terrazze con il sistema delle dighe harrah

Ampi sistemi di organizzazione delle valli per mezzo di dispositivi d’acqua.

Lungo il corso naturale dell’acqua, le dighe chiamate masraf, intercettano i flussi d’acqua che corrono giù per il pendio e li deviano sulle superfici delle terrazze coltivate situate su entrambi i lati.

A large system of organization of valleys by means of water devices. A long the natural water course the dams called ”masraf” intercept the flows running down the steepest slope and deviate them towards the cultivated terraces on both sides.

Yemen del nord – Grandi terrazzamenti

Yemen del nord – Grandi terrazzamenti

Yemen del nord – Grandi terrazzamenti

Sistema di terrazzamenti per la protezione e la coltivazione del pendio. Le prese d’acqua deviano i flussi dal loro corso naturale e li dirigono lungo i muri verso le terrazze.

Torri e costruzioni in pietra, sono disposte a difesa delle coltivazioni.

Terracing system for the protection and cultivation of the slope. The water intakes deviate the flows from their natural course and direct them along the walls on the terraces. Towers and stone buildings are placed to defend the cultivations.

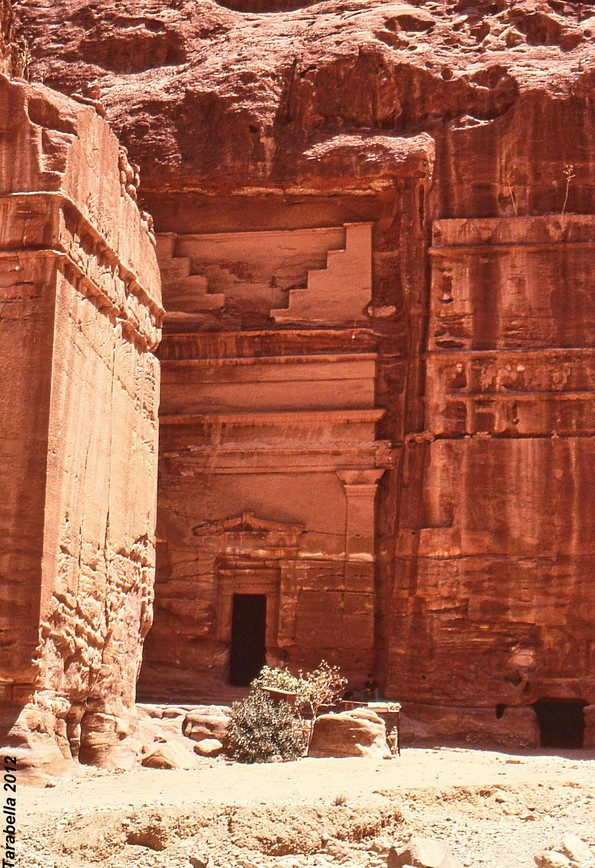

Petra (Giordania)

Il sistema di terrazzamenti chiamati khaur, tipico dell’agricoltura nabatea e usato anche nel deserto del Negev, si può ancora notare tra le architetture monumentali di Petra.

Negli ambienti rurali, erano semplici terrazzamenti semicircolari di contenimento dei suoli, mentre in aree urbane diventarono un sistema di costruzione più complesso.

Petra ( Jordan)

The stone terracing system called ” khaur”typical of the Nabataean agriculture, used in the Negev desert, are still visible. In rural environments, they are mere semi-circular terracing system which retain the soil, where as in urban areas they are more complex building system.

Some examples of these system made which carbon layers to filter water and make it fit for drinking have been discovered.

Petra (Giordania) Resti di terrazzamenti in pietra all’interno della città Nabatea

Agricoltura Inca -Lago Titicaca (Perù)

I contadini inca hanno dovuto affrontare le difficoltà di coltivare in terreni impervi nelle strette valli scavate dai fiumi che scorrevano tra i monti.

Sugli altopiani il clima era troppo freddo e li rendeva meno adatti all’agricoltura.

Per aumentare la superficie coltivabile , gli Inca utilizzarono numerose tecniche che permettevano di coltivare i fianchi delle colline.

Anden

Sono terrazze agricole artificiali utilizzate per recuperare terreno adatto alla semina sui pendii andini.

Permettono di sfruttare meglio l’acqua delle piogge e dell’irrigazione facendola circolare in canali comunicanti tra i diversi livelli.

Con questo sistema si evitava anche l’erosione idraulica del suolo.

Agriculture Inca-Titicaca Lake (Perù)

The farmers Inca have faced difficulties to grow in rough terrain in the narrow valleys carved by rivers flowing from the mountains. In the highlands, the weather was too cold and it made them less suitable for agriculture. To increase arable land, the Incas used it numerous techniques that allowed to cultivate the hillsides.

Anden

Are artificial agricultural terraces used to recover land suitable for sowing on the Andean slopes. Allow you to make better use of the water of rains and irrigation circulating in connecting channels between the different levels.

With the system it is also avoided the hydraulic soil erosion.

Anden (Perù)

Moray – Valle Sacra degli Incas ( Perù)

Il sito di Moray contiene una serie di terrazzamenti circolari concentrici che formano una sorta di anfiteatro.

L’ipotesi indica questo sito come un laboratorio per lo studio dell’adattamento delle diverse specie di coltivazioni a varie quote di altitudine.

Moray – Sacred Valley of the Inca (Perù)

The Moray site contains a series of circular concentric terraces forming a sort of amphitheater. The hypothesis indicates this site as a laboratory for the study of adaptation of the different species of crops at different altitude shares.

Moray ( Perù ) Valle Sacra degli Inca

Colca Valley (Perù)

The Colca Valley is situated in the Andes, in the west of the Caylloma province, in the Department of Arequipa, between 2200 and 4500 metres of altitude, which represents the highest limit of livestock rearing. Huge mountains dominate the valley which lies in a canyon over 100 km long, and carved by the river Colca. While since the pre-Inca period, the local population cultivated this land on terraces, relying on specific situations found at different altitudes, this technique was abandoned after the colonial period. The remaining terraces are neglected and little irrigated. The DESCO Peruvian ONG has started a rehabilitation of these terraces and their irrigation channels and to sensitize the population on their quality. The results are convincing: the productivity of land and crop yields have increased, erosion and water losses are reduced, the landscape is arranged and attractive to tourists. Lofty mountains dominate the valley which lies in a canyon, over 100 km long, hewn by the Colca river. Long before the Inca period, the local population cultivated their land on terraces, taking into account specific conditions at different altitudes, this technique was abandoned after the colonial period. The remaining terraces are neglected and little irrigated. The DESCO Peruvian ONG has started a rehabilitation of these terraces and of their irrigation canals, informing the population on their importance. The results are positive: soilproductivity and crop yields have increased, erosion and water losses are reduced, the landscape is well organized and made attractive to tourists. The Colca valley was originally inhabited by the Collahuas who had developed a production system based on terraces and particular irrigation methods. Even before the period of the Incas, the local population profited of the different qualities of the land at various altitudes. Approximately 60.000 people fulfilled their needs solely through the resources of the valley (agriculture and animal husbandry), but this technique was abandoned after the colonial period and the population dwindled to only 6000. From the ecological point of view, this area is rich varieties of species: up to 15 different ecosystems have been identified. In terms of agricultural production, there are however three major systems: the area of the high Andes, more than 3800 m high, reserved to the breeding of camelids, the intermediate zone, between 3000 and 3800 m suitable for farming and agriculture associated with animal husbandry, and the lower area, more suitable for the cultivation of fruit. After the colonial period the productivity of the land in the valley of Colca diminished greatly. According to official estimates, 30% of arable land has been lost entirely due to the degradation of terraces and a lack of maintenance of the irrigation system. Poor land management has also contributed to the loss of fertility. In fact, people have abandoned traditional farming techniques, which consisted in enriching the soil through mulching (covering the flower with protective layer), crop rotation, mixed farming or compost. Short term agricultural production, maximizing immediate yields has been given priority to the detriment of sustainable development, and this has exhausted the resources and degraded soils. The felling of trees for the use wood for fuel is another cause of desertification. Mountainous areas are characterized by a severe lack of water, steep terrain and difficult weather conditions (frost, low humidity). The total annual rainfall is 350 mm, 60% of this much occurs between January and March thus allowing only one crop per year. Small properties are widespread and each household owns an average of 1.2 hectares, divided into small parcels distributed along different slopes. Generally the inhabitants grow from eight to sixteen different plant species, the most common are corn, beans, potatoes, barley and quinoa. Traditional techniques to compensate for the difficulties of this environment consist in terracing, irrigation networks and adaptation of crops to the microclimate of each altitude. DESCO has worked out its project in 1992 in the province of Lari, Colca Valley, between 3,200 and 4,500 m of altitude. The objectives were to rehabilitate the terraces, improve irrigation facilities and introduce the practice of agroforestation in the region. The results expected were the improvement of agricultural productivity, public awareness of population and ecological approach to the revaluation of local traditional knowledge. The advantages of terraces go beyond the simple possibility of ploughing a slope. Terraces are effective for controlling erosion and improving water management. They help to break up the moisture in the soil thus reducing the risk of frost. Moreover, they allow to better exploit the microclimatic and ecological peculiarities of various altitudes. The rehabilitation of terraces in the Andes requires the restoration of three fundamental components. First the stone walls , which support the terraces. After digging a trench 50 cm deep along the contour line, large and heavy boulders are laid that form the foundation and give stability to the whole. On the surface, the wall is raised after laying stones of different sizes on top of each other, slightly jutting in the direction of the slope. The height of the wall depends on the width of the terrace. Some smaller stones are then added in the interstices of the larger blocks and behind the wall to reinforce it.The terraces themselves, are essentially created with the earth in the sloping lot which needs flattening. However, some are more elaborate than others and consist of different layers: a base bed consisting of large stones serves as a filter for draining irrigation water, an intermediate layer of small stones covered with sand and clay, and a final top layer of 50-80 cm of fertile land. The terraces are slightly jutting to allow water to seep slowly without causing erosion. Finally, access roads, consisting of small steps that cross-link the terraces. Usually these steps are inserted in the stone wall. Even the irrigation canals have been rehabilitated. Water from springs is collected in a reservoir upstream, then distributed by means of stone gutters from a terrace to another. The agro-forestation is greatly encouraged on the terraces. It consists on growing at the same time the annual species, such as cereals, and persistent species such as fruit trees. This method of production adds to the ecological and economic benefits, since it allows the farmers to diversify their products, thus enriching the soil. For the maintenance of terraces, it is useful to plant woodland species at the foot of the wall in order to support it and act as windbreaks. The species of trees recommended for their properties are thorns and cherry trees, cypresses and pines.

La Ciudad Perdida – Sierra Nevada (Colombia)

The Lost City – Sierra Nevada (Colombia)

La Ciudad Perdida – Sierra Nevada (Colombia)

La nativa comunità dei Tairoma, a partire dall’XII secolo, costruì una delle città più importanti dal punto di vista dell’adattamento in un ambiente ostile caratterizzato da un terreno ripido e forti precipitazioni; piove quasi tutto l’anno e le temperature vanno dai 17 ai 24 gradi.

Il sito si estende su una superficie di venti ettari ed è circondato da numerose vie navigabili interne.

Le rovine si trovano tra i novecento ed i milleduecento metri sul livello del mare e sono formate da 169 terrazzamenti con muri di contenimento in pietra appoggiati sul profilo della montagna.

Sono dotate di percorsi, scale e canali di pietra che s’intrecciano con aree verdi.

Le terrazze che formano la Ciudad Perdida seguono il crinale della montagna formando il nominato asse centrale dove si trovavano il potere politico e religioso.

I terrazzamenti sono stati costruiti per ottenere una superficie piana superiore e, su entrambe i lati del pendio, ci sono terrazze che sono servite come base per la costruzione di case.

La parte che oggi noi vediamo, sono gli anelli di pietra che formavano le fondazioni degli edifici con superfici che vanno da sei ad un massimo di duecento metri quadrati.

Sono presenti edifici semicircolari, situati in periferia, probabilmente utilizzati come magazzini mentre, lungo l’asse principale, sono stati scoperti resti di edifici rettangolari di ampie dimensioni.

Di grande importanza sono le pareti di contenimento in lastre di pietra tenute insieme da rocce rettangolari o arrotondate chiamate tensors la cui funzione era quella di sostenere il carico della parete.

La tecnica impiegata nella costruzione di terrazze consisteva nel tagliare il pendio verticale a forma di zoccolo riempendolo di materiale di risulta e supportandolo sul lato opposto a quello della pendenza.

Il contenimento delle pareti variava a seconda della pendenza.

Sono state utilizzate, oltre che come terrazze, anche come percorsi e scarichi per l’acqua piovana.

Per la costruzione delle pareti venivano impiegate solo argille selezionate.

Nelle parti superiori le argille erano permeabili per facilitare la penetrazione dell’acqua nelle parti più basse.

I canali

La Ciudad Perdida presenta opere idrauliche con canali che controllavano il flusso di acqua piovana evitando l’erosione e il dilavamento dei materiali.

Si possono vedere parti lisce fiancheggiate da pietre che avevano la funzione dievitare l’accumulo di fango.

The ruins of the Ciudad Perdida, situated on the northern slope of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, were discovered by J. Alden Mason during his expeditions of1922-23. Today the Ciudad Pedidida is a National Monument. The ruins of this ancient settlement are grouped on a bank of the Buritaca river. Here, beginning from the 11th century the native community of the Tairona built one of the most important cities from the point of view of adaptation to a hostile environment, characterized by a steep terrain and heavy rainfalls: it rains almost all year round and rainfall levels range from 2,000 up to 4,000 mm per year, with temperatures spanning from 17 ° to 24 ° C. The site covers an area of 20 hectares and it is surrounded by various waterways. The ruins are located between 900 and 1,200 meters above sea level, on 169 terraces, with their containment walls which rest on the profile of the mountain, with paths, stairs and channels, made of stone, intertwined with green areas . The terraces forming the Ciudad Perdida follow the “ridge” of the mountain, forming what was called the central axis where the buildings of the political and religious power were located. The terraces were built to obtain a greater level surface. On both sides of the slope there are terraces which served as the basis for the construction of houses. Today we see the rings of stone that formed the foundations of buildings, with an area ranging from a minimum of 6 to a maximum of 200 square meters. There are some semi-circular buildings, probably used as warehouse, located in the suburbs. While along the main axis the remains of rectangular buildings of large dimensions were found.

The terraces

Of great importance are the containment walls made of slabs of stone held together by rectangular or rounded rocks, called “tensors” whose function was to support the load of the wall. The native Koguis called them sandinkamas, which means “Guardians of the wall.” The construction technique employed in the building of terraces consisted in cutting the slope vertically in the shape of hooves, which were filled with the resulting material, and supported on the opposite side to that of the slope by sophisticated walls. The containment walls vary depending on the slope. In addition to the terraces, the walls were also used as paths and drains for rainwater. In the construction of the walls no cohesive material was used, but only selected clays. In the upper parts, permeable clays were used in order to facilitate the penetration of water into the lower parts.

The canals

The Ciudad Perdida presents remarkable canal works, with which it was possibile to control the flow of rainwater thus avoiding erosion and the washing away of materials. We observe smooth parts, lined with stones which had the function of avoiding the accumulation of mud.

Footpaths

Another very interesting aspect of Tairona settlements are the paths, which extended to the coast, linking the various provinces. In Ciudad Perdida, the path of the central axis has a complex structure, which in some places reaches a thickness of 0.6 m and a width of 2 m. There are also simple paths, consisting of unfashioned stones. Both the main and secondary routes are built with stone slabs of various sizes and in some places some large stones called “retirement plans” are found which have various functions, including that of mitigating the force of rainwater. Some stones presents some of the cuts and served as benchmarks by.

Giardini terrazzati

Giardini pensili – Gravina di Puglia (Puglia)

Giardini pensili organizzati nell’alveo della gravina.

Ai piedi della collina di Botromagno, si possono ancora vedere i sistemi idraulici con le vasche di raccolta dell’acqua.

Sullo sfondo, il ponte acquedotto sul torrente Gravina, collega ancora oggi le due sponde.

Terraced gardens

Hanging gardens – Gravina di Puglia (Apulia)

Roof gardens arranged in the channel of the gravina. At the foot of the hill Botromagno, you can still see the hydraulic systems with water collection tanks. In the background, the aqueduct-bridge over the river Gravina, still connects the two banks today.

Gravina di Puglia (BA) Terrazzamenti sulla gravina

Giardini terrazzati a Palagianello (Puglia)

La trama dei terrazzi e giardini, ancora conservata in alcune parti della gravina, dimostra come questo sistema originario sia la matrice del tessuto urbano.

Terraced gardens to Palagianello (Apulia)

The plot of the terraces and gardens, still preserved in some parts of the gravina, shows that this is the original system of the urban matrix.

Giardini terrazzati a Massafra (Puglia)

Giardini pensili organizzati sulle sponde della gravina.

Il letto del torrente passa al di sotto dei terrazzi coltivati.

Terraced gardens to Massafra (Apulia)

Roof gardens organized on the banks of the gravina.

The bed of the stream passes under the cultivated terraces.

Gravina di Massafra (Puglia) Le sponde della gravina sono organizzate in terrazzi artificiali coltivati

Giardini pensili a Matera (Basilicata)

I Sassi di Matera rappresentano uno degli aggregati urbani più antichi al mondo.

La loro esistenza è fondata sull’ingegnoso sistema di raccolta delle acque.

Nel tempo, i pendii della maestosa gravina, vennero scavati, lavorati e scolpiti per formare cunicoli, cisterne e articolati ambienti sotterranei.

Il tufo tagliato in blocchi, serviva per la costruzione di muri a secco, terrazzamenti, strade,scale e percorsi che corrispondono ai tetti delle abitazioni sottostanti.

Le case, i terrazzi e i giardini si svolgono in gironi concentrici e circondano l’alveo di un torrentello di drenaggio ora coperto.

I vari livelli di ipogei si collegano internamente attraverso pozzi e strutture verticali per l’aerazione.

Si possono rilevare anche oltre dieci piani di grotte sovrapposte dotate di cisterne a campana unite da canali.

Il numero delle cisterne, assai superiore rispetto al numero delle grotte, testimonia che l’organizzazione del territorio era composta di giardini agricoli ricavati sui terrazzi scavati nella roccia che necessitavano di grandi quantità d’acqua.

L’evoluzione da struttura pastorale in organizzazione urbana, crea il prolungamento in avanti delle grotte laterali formando il ”lamione”.

Il primitivo orto irrigato diventa l’aia comune con la cisterna sottostante dove viene convogliata l’acqua dai tetti delle abitazioni organizzate per la raccolta.

I tetti delle case inferiori arrivano fino al ciglio del gradone superiore oppure i giardini delle case prospicenti creano il paesaggio urbano a terrazzi degradanti.

Il tetto di una grotta diventa una strada oppure un giardino pensile dell’abitazione sottostante.

Anche la più piccola superficie piana viene sfruttata per coltivare giardini pensili e piccoli frutteti.

Questa trama di terrazzi e giardini, si può ancora scorgere in alcuni punti della città a testimonianza di come questo sistema originario sia la matrice del tessuto urbano.

Hanging gardens to Matera (Basilicata)

The Sassi of Matera are one of the oldest urban centers in the world.

Their existence is founded on the ingenious water collection system.

Over time, the majestic slopes of the gravine, were dug, worked and sculpted to form tunnels, tanks and articulated underground environments.

The tuff cut into blocks, needed for the construction of dry stone walls, terraces, streets, stairs and paths that correspond to the roofs of the houses below.

The houses, the terraces and the gardens are carried out in concentric circles, surrounding the bed of a drainage stream now covered.

The various levels are connected internally through underground wells and vertical structures for ventilation.

It can also detect over ten floors of superposed caves equipped with channels joined to bell tanks.

The number of tanks, much higher than the number of caves, testifies that the organization of the territory was composed of agricultural gardens on terraces carved into the rock obtained that needed large amounts of water.

The evolution from pastoral structure in urban organization, creates the extension forward of the side caves forming the ” lamione ”.

The primitive vegetable garden watered become the common farmyard with the cistern below where the water is conveyed from the roofs of houses organized for the collection.

The roofs of the lower houses come to the edge of the upper terrace steps or the gardens of the houses facing and create the urban landscape sloping terraces.

The roof of a cave becomes a road or an area below the roof garden.

Even the smallest flat surface is exploited to cultivate hanging gardens and small orchards.

This plot of terraces and gardens, it can still be seen in some parts of the city as evidence of how this original system is the urban matrix.

Matera – Scampoli di giardini terrazzati che dalla civita sovrastano il Sasso Barisano

Matera – Giardini pensili nel Sasso Caveoso

Matera – Giardino pensile nel Sasso Barisano

Matera – Tra le abitazioni in tufo dai colori pastello spunta il verde dei giardini terrazzati

Giardini pensili alle Cinque Terre (Liguria)

Nelle zone come la Liguria, dove il territorio è limitato, ogni singolo lotto di terra viene sfruttato per la coltivazione di piccoli orti e alberi da frutto.

Roof gardens to the Cinque Terre (Liguria)

In areas such as Liguria, where the territory is limited, each plot of land is used for cultivation of small vegetable gardens and fruit trees.

Cinque Terre ( Liguria) Giardino pensile sulla piccola baia di Corniglia

Cinque Terre ( Liguria) Giardino pensile con limonaia

Giardini pensili a Lerici (LIguria)

Giardini a terrazza – Locorotondo ( Puglia)

I giardini di pietra terrazzati, circondano il borgo di Alberobello e arricchiscono il paesaggio intorno alla cittadella pugliese.

Terraced gardens – Locorotondo (Apulia)

The stone terraced gardens, surrounding the village of Alberobello and enrich the landscape around the Apulian citadel.

Locorotondo (Puglia) Giardini terrazzati sotto l’abitato

Giardino terrazzato – Dubrovnik (Croazia)

Giardino pensile sulla costa croata. Oltre alla funzione di manutenzione del suolo e alla coltivazione degli ortaggi, questo sistema di terrazze viene utilizzato come giardino pensile per fiori e piante.

Terraced garden – Dubrovnik (Croatia)

Roof garden on the Croatian coast. In addition to the maintenance function of the soil and the cultivation of vegetables, this system of terraces is used as a roof garden for flowers and plants.

Dubrovnik (Croazia ) Giardino pensile

Terrazzi e scale in pietra – Alta Versilia (Toscana)

I pendii dell’Alta Versilia sono organizzati in terrazzi artificiali coltivati collegati da scale in pietra.

Le strutture in pietra a secco, proteggono il suolo dalle frane provocate dalle abbondanti piogge.

Terraces and stone staircases to Versilia High(Tuscany)

The slopes of the High Versilia are organized in cultured artificial terraces connected by stone stairs.

The stone structures dry, protect the soil from landslides caused by heavy rains.

Antichi terrazzamenti montani nell’ Alta Versilia (Toscana)

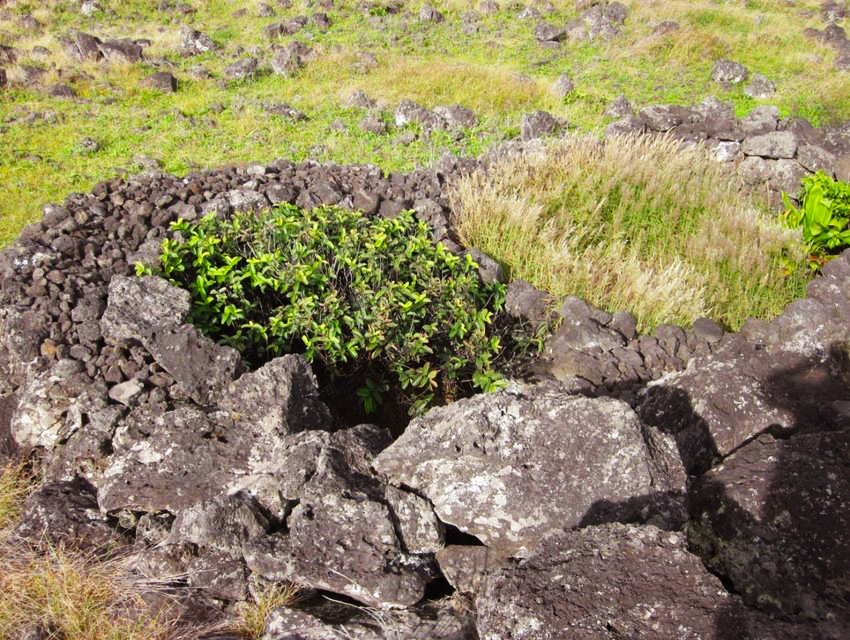

Strutture in pietra – Grottaglie (Puglia)

La gran parte delle strutture in pietra a secco diffuse nelle terre aride della Puglia, contribuiscono alla produzione di acqua.

Gli accumuli di massi spugnosi intorno all’olivo, assorbono la brina notturna e riforniscono di umidità il terreno e la pianta.

Stone structures – Grottaglie (Apulia)

Most of the dry stone structures spread in the arid lands of Apulia, contribute to water production.

The boulders spongy accumulations around the olive tree, absorb the night dew and supply of moisture the soil and plant.

Grottaglie ( Puglia) Recinto di pietra intorno all’olivo

Isola di Pasqua, coltivazioni protette nelle conche di pietra lavica

Isola di Pasqua, i recinti di pietra lavica proteggono le piantine dal vento e dal calore

Jazzo rupestre – Matera (Basilicata)

Sui pendii scoscesi gli imponenti muri a secco dello jazzo rupestre, proteggono dagli effetti delle piogge e creano lo spazio per le coltivazioni.

Rock jazzo – Matera (Basilicata)

On the steep slopes of the towering stone walls of rock jazzo, protect against the effects of rain and create the space for crops.

Matera (Basilicata) Jazzo rupestre nella gravina

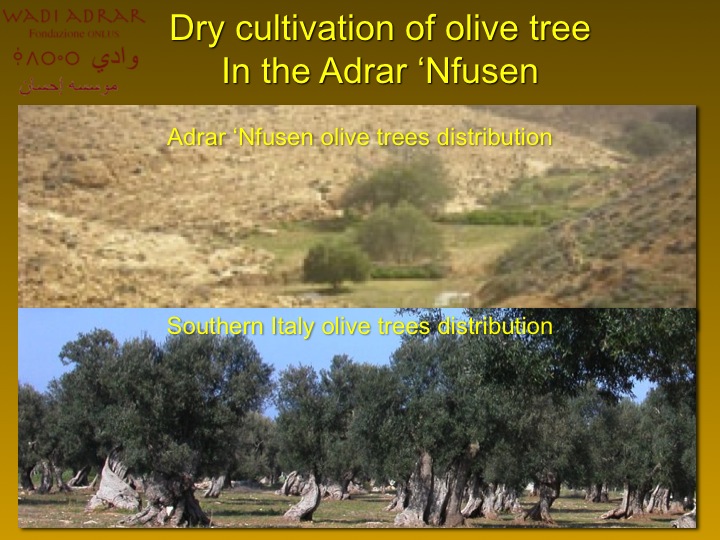

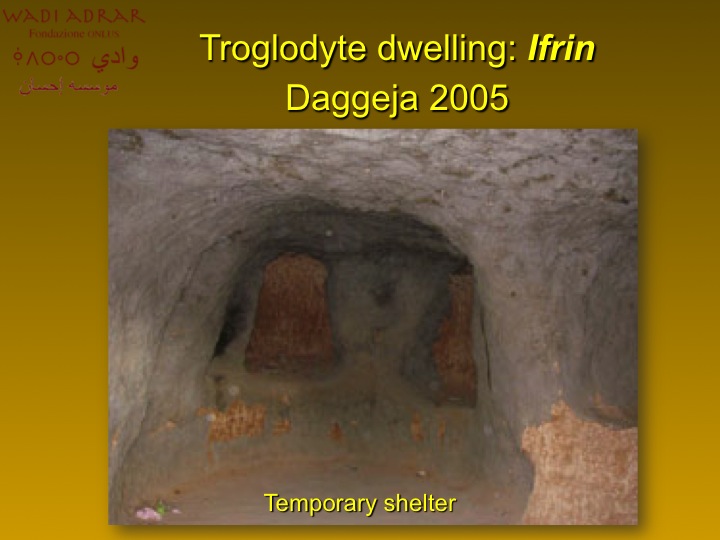

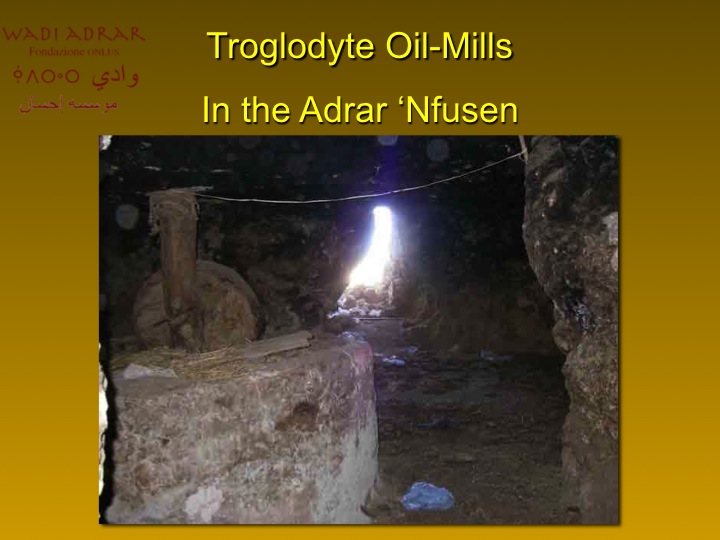

Wadi Adrar ( Libia)

(Wadi Adrar Fondazione O.N.L.U.S.)

Coltivazioni dell’olivo nel deserto sassoso del Jebel Nafusah

In ambienti estremamente aridi come il deserto libico del Jebel Nafusah, è possibile far crescere la pianta dell’olivo con particolari ma, semplici tecniche tradizionali.

Questo luogo, così inospitale, privo di vegetazione, caratterizzato da una rete di wadian secchi, è apparentemente privo di forme di vita.

All’interno di uno wadi, vengono costruiti dei muri a secco chiamati fekka, inizialmente piuttosto piccoli.

Il vento e le sporadiche piogge accumulano la polvere lungo i muretti che vengono, così, innalzati.

Questi detriti si trasformano, tramite l’azione dei batteri, in humus chiamato hamri.

Quando l’humus fertile è sufficiente per formare una superficie coltivabile detta tabiya, viene introdotto un seme di olivo.

Il muro a secco viene alzato, con il crescere della pianta, fino a che la superficie coltivata contiene l’humus sufficiente per la sopravvivenza di una pianta adulta che inizia a fruttificare.

Le piantagioni di olivi lungo gli wadian sono molto rade.

L’olivo non viene potato ed assume una forma a cespuglio basso che produce frutti piccoli e magri a causa dei lunghi periodi di siccità e dall’ambiente ostile di questo deserto roccioso.

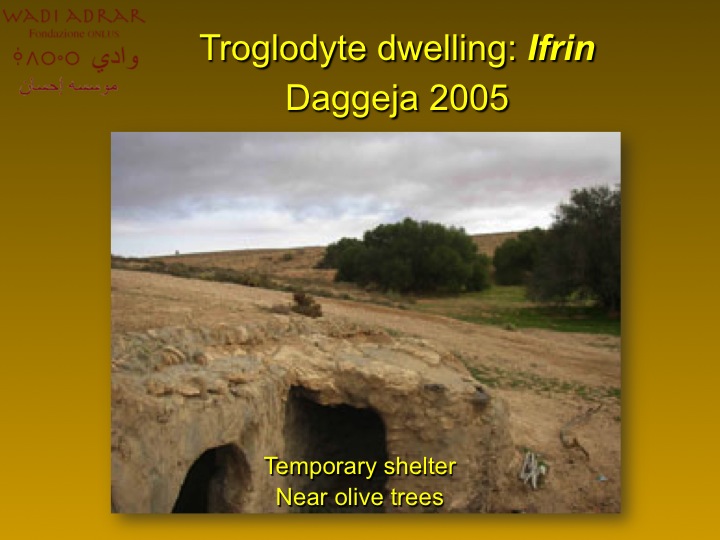

Gli insediamenti trogloditi disseminati nella zona sono la testimonianza della permanenza di popolazioni stanziali stagionali che occupavano questa parte di deserto durante la raccolta delle olive.

Dopo il raccolto le olive vengono trasportate nei frantoi ( masra zaituna) per la maggior parte trogloditi dove, mediante macine in pietra, viene ottenuto l’olio.

L’olio viene versato nelle giare e conservato nei granai fortificati chiamati qars.

Il deserto, ancora una volta, riesce a stupirci regalandoci frutti e raccolti inaspettati.

Orti – giardini

Oasi di Timimoun (Algeria)

All’ombra del palmeto, si crea uno spazio diviso geometricamente che corrisponde, in natura, al rapporto stretto tra microcosmo e macrocosmo.

All’interno dei campi, si coltivano gli ortaggi.

Gardens – vegetable gardens

Oasis of Timimoun (Algeria)

The shade of the palm grove, it creates a geometrically corresponding divided space, in nature, the close relationship between microcosm and macrocosm.

Within the camps are cultivated vegetables.

L’acqua raccolta nei bacini di stoccaggio viene utilizzata per l’irrigazione delle singole particelle di terreno

Coltivazioni nell’oasi di Timimoun (Algeria)

Oasi – Ripartitore d’acqua

Orti – Beit Bous (Yemen del nord)

Il paesaggio yemenita dietro l’insediamento di pietra di Beyt Bous.

I campi sono coltivati a ortaggi e cereali.

Vegetable gardens – Beit Bous (North Yemen)

The Yemeni landscape behind the Beyt Boys stone settlement.

The fields are planted with vegetables and cereals.

Coltivazioni intorno a Beit Bous (Yemen del nord)

Orti cittadini – Sana’a (Yemen)

Ai piedi del Jebel Nuqum (montagna), si estende la città di Sana’a circondata da estesi orti-giardini coltivati a verdure, ortaggi e alberi da frutto.

Citizens vegetable – gardens – Sana’a (Yemen)

At the foot of Jebel Nuqum (mountains), lies the city of Sana’a surrounded by extensive vegetable – gardens planted with vegetables, fruit trees and vegetables.

Orti e coltivazioni intorno alla città di Sana’a (Yemen)

Uso delle inondazioni a Shibam – Hadramaut (Yemen del sud)

La valle dell’Hadramut e l’antica città murata di Shibam, sono circondate da canali e argini in un sistema tradizionale di condivisione delle piene e delle coltivazioni degli orti-giardini.

La maggior parte di questi giardini situati in bacini, sono oggi abbandonati.

Use of the floods in Shibam – Hadramaut (South Yemen)

The valley of Hadramut and the ancient walled city of Shibam, they are surrounded by canals and embankments in a traditional system of sharing of floods and crops of horticultural gardens.

Most of these gardens located in the basins, are abandoned today.

Giardini nelle depressioni di sabbia di Shibam – Hadramaut (Yemen del sud)

Giardini cintati

Giardino nel borgo di Dubrovnik (Croazia)

Nella città fortificata croata, si creano piccoli giardini tra muri di pietra per fiori, piante e orti.

Walled gardens

Garden in the village of Dubrovnik (Croatia)

In the Croatian walled city, creating small gardens between stone walls for flowers, plants and vegetable gardens.

Giardino chiuso nella cittadina croata di Dubrovnik

Giardini di terra cruda – Rhoda (Yemen del nord)

Gli orti e le coltivazioni della zona di Rhoda, sono circondati da muri di terra cruda.

All’interno dell’area coltivata, ci sono ambienti dove vengono immagazzinati i raccolti.

Sulla destra della foto, si nota la torre chiamata nuba, a difesa delle coltivazioni e simbolo del villaggio.

Raw land gardens – Rhoda (North Yemen)

Vegetable gardens and crops of Rhoda area, are surrounded by earthen walls.

Cultivated area inside, there are environments where they’re stored crops.

On the right of the photo, you can see the tower called Nuba, in defense of the crops and the village symbol.

Rhoda (Yemen del nord) Coltivazioni cintate da muri di terra cruda

Giardini in crateri

Conche dunari artificiali – Sahara algerino

Con le oasi artificiali del Sahara, si ottengono enormi situazioni di modificazione del paesaggio, grazie a questi grandi crateri di sabbia.

Questo tipo di oasi permette alla sabbia del deserto naturale, di continuare a scorrere e fluire, dopodichè viene trasformata e modulata.

All’interno di queste forme ad imbuto, si condensa l’umidità, protetta dalla chioma delle palme e perimetralmente dalle stesse dune.

Gardens in craters

Formation of protective dunes (Algerian Sahara)

With artificial oases of the Sahara, you get huge landscape modification situations, thanks to these great craters of sand.

This kind of oasis allows the sand of the natural desert, to continue to flow and flow, after it is transformed and molded.

Within these funnel-shaped forms, it condenses moisture, protected by the canopy of palm trees and along the perimeter of the same dunes.

Sahara algerino – Coltivazioni di palme all’interno di conche artificiali di sabbia

Coltivazioni in crateri di sabbia nel Sahara

Giardini in crateri a Lanzarote (Spagna)

Gardens in craters in Lanzarote (Spain)

Vigneti a La Geria – Lanzarote (Spagna)

Ortocolture con alberi d’alto fusto

Oasi Timimoun (Algeria) e Nefta (Tunisia)

I giardini delle oasi, sono tipicamente coltivati a tre livelli : alberi che fanno ombra (palme), alberi da frutto, cereali o verdure.

I fruttiferi campi, sono ordinati in piccolo pezzi di giardino chiamati jenna.

La forma geometrica delle coltivazioni corrisponde a precise regole che sono alla base della vita nell’oasi.

Ortocolture with tall trees

Oasis Timimoun (Algeria) and Nefta (Tunisia)

The oasis gardens are typically planted at three levels: shady trees (palm trees), fruit trees, grains or vegetables.

Interest-bearing fields, are sorted into smaller pieces of garden called ”jenna”.

The geometric form of the crops corresponds to precise rules that are the basis of the oasis life.

Nell’oasi, l’acqua viene raccolta in bacini di stoccaggio e utilizzata dall’agricoltore per l’irrigazione delle singole parcelle di terreno

Nell’oasi, la trama del territorio, l’orientamento delle abitazioni e dei villaggi, l’organizzazione dei giardini sono parte di una sfera di segni in cui, tutte le cose, hanno un senso

Coltivazioni nell’oasi di Nefta (Tunisia)

Giardini galleggianti

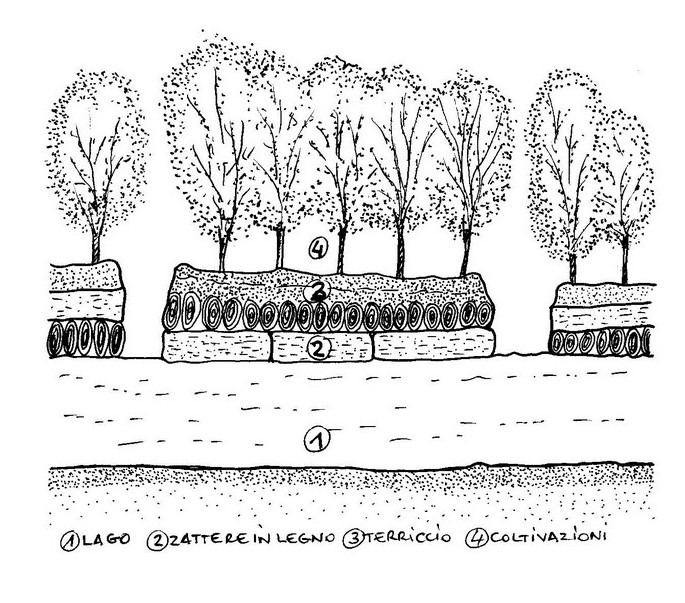

AGRICOLTURA MESOAMERICANA

Chinampa ( Messico)

Tecnica atzeca per la formazione di giardini galleggianti organizzati su zattere in laghi di acqua dolce.

Gli atzechi costruirono un complesso e accurato sistema di dighe, attraverso il quale regolavano il travaso di eccedenza di acqua da un lago all’altro.

Floating gardens

Chinampa (Mexico)

Aztec technique for the formation of floating gardens arranged on rafts in freshwater lakes.

The Aztecs built a complex and accurate system of dams, through which regulated the decanting of excess water from a lake to another.

Giardini galleggianti (Messico)

Sezione di un giardino galleggiante

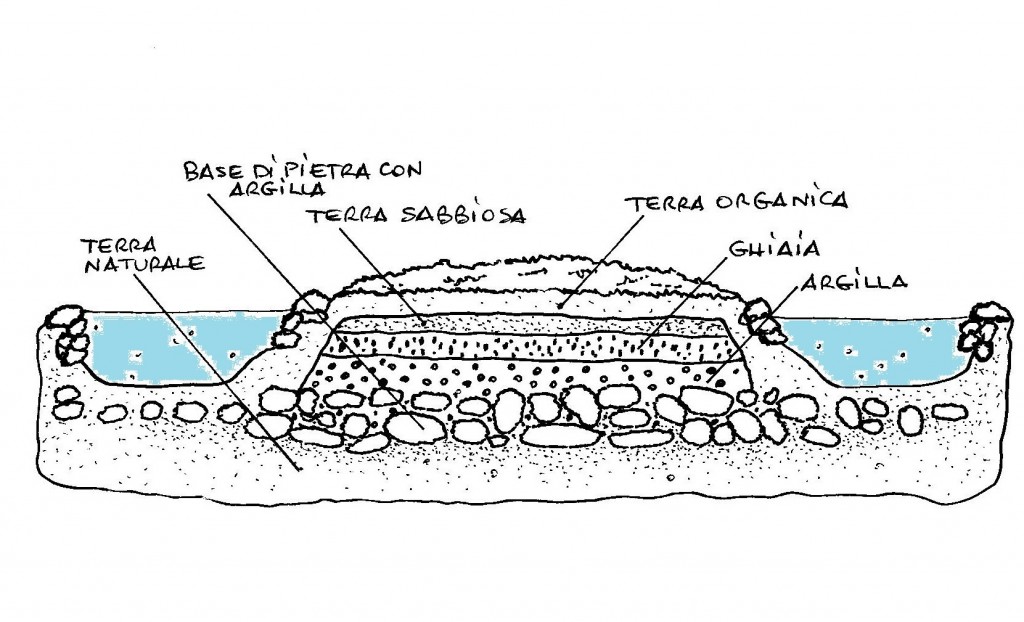

Waru Waru o Camelon – Lago Titicaca (Perù)

Sono aree artificiali costruite sulle rive del Lago Titicaca.

Consistono in un trattamento della collina in modo da migliorare lo sfruttamento dell’acqua in zone in cui le inondazioni sono frequenti.

In modi diversi vengono tracciati tra loro solchi artificiali per proteggere le piante, per facilitare il drenaggio durante le piogge, le inondazioni, le irrigazioni e per diminuire il freddo notturno evitando il congelamento delle coltivazioni.

Waru Waru or Camelon – Titicaca Lake (Perù)

Artificial areas are built on the shores of Lake Titicaca.

They consist of a treatment of the hill in order to improve the exploitation of water in areas where floods are frequent.

In different ways they are drawn to each other artificial furrows to protect plants, to facilitate drainage during the rains, floods, irrigation and to decrease the cold night avoiding the freezing of crops.

Schema del sistema agricolo waru waru – Lago Titicaca

Sistema waru waru

Strade-torrenti

Wadi Dhar (Yemen)

Il panorama di strade, giardini e coltivazioni è creato grazie alle tecniche di distribuzione delle strade-torrenti.

Le quantità d’acqua emessa si riversa dentro i giardini situati tra le mura e le strette stradine.

L’intero sistema funziona con la gravità e determina una rigorosa organizzazione che lavora a pieno solo quando avvengono le sporadiche inondazioni ed i percorsi si trasformano in corsi d’acqua.

Torrent-streets

Wadi Dhar (Yemen)

The landscape of road, gardens and cultivations created thanks to the water distribution tecnique of the torrent-streets. The water intakes open into the gardens situated between the walls of the narrow streets. The whole system warks by gravity and determines a rigorous organization which fully functions only when of the sporadic floods occur and the pathways turn into watercourse.

Wadi Dhar (Yemen) Strada-torrente

Valle dello M’Zab ( Sahara algerino)

La risorsa d’acqua principale di questa valle proviene dalle inondazioni che si verificano ogni due,

tre anni e per questo il territorio è organizzato in modo tale da sfruttare questo evento.

Le grandi prese d’acqua intercettano il flusso d’acqua e lo distribuiscono nei campi coltivati.

Le strade strette, racchiuse tra le alte mura che circondano i giardini, diventano torrenti che convogliano l’acqua.

Le aperture sono inserite nelle pareti e aspirano la quantità d’acqua necessaria per ogni giardino attraverso la serie di canali e bacini che garantiscono l’irrigazione del verde.

M’Zab Valley (Algerian Sahara)

The main source of water in this valley comes from the floods that occur every two,

three years and for this reason the setting is arranged so as to exploit this event.

The large water intakes intercept the flow of water and distribute it in the cultivated fields.

The narrow streets, enclosed by the high walls surrounding the gardens, they become rivers that convey the water.

The openings are inserted in the walls and aspire the amount of water required for each garden through the series of channels and reservoirs which ensure the irrigation of the green.

Strada-torrente nella Valle dello M’zab

Giardini creati sulle rive dei fiumi (wadi)

Oued Roufi Algeria)

L’oasi di oued Roufi, usa la protezione delle alte mura del canyon ed il letto dello wadi per le coltivazioni.

L’approvvigionamento d’acqua proviene dai flussi sotterranei e dalle sporadiche inondazioni.

Gardens created on the sides of the riverbed (wadi)

Oued Roufi (Algeria)

A wadi oasis that used the protection of the walls of the canyon and the wadi bed for the cultivations. The water supply comes from the underground flow and the sporadic floods.

Coltivazioni sulle sponde dell’oued

Wadi Dwan (Yemen)

Nelle valli dell’Hadramut, i campi coltivati ed i fitti palmeti sfruttano il letto del fiume per attingere acqua mediante le infiltrazioni sotterranee.

Anche in questa zona, le inondazioni sono rare.

Wadi Dwan (Yemen)

In dell’Hadramut valleys, cultivated fields and dense palm groves exploit the riverbed to draw water through underground seepage.

Also in this area, the floods are rare.

Wadi Dwan (Yemen) Coltivazioni sulle sponde del wadi

Wadi Gazwa (Yemen)

Nella zona nord dello Yemen, la leggera pendenza dello wadi, permette di coltivare nel letto del fiume con il sistema a terrazze.

Oltre alle acque sotterranee e delle piene, i muri a secco trattengono l’umidità prodotta sulla superficie delle terrazze.

Wadi Gazwa (Yemen)

In northern Yemen area, the slight slope of the wadi, can be cultivated in the riverbed with the system in terraces.

In addition to groundwater and flood, the dry stone walls retain moisture produced on the surface of the terraces.

Wadi Gazwa (Yemen) Terrazze sul fondo dello wadi