Le strutture ipogee sacre sono architetture scavate nella roccia. Alcune di queste, inizialmente nate come edifici religiosi, si sono trasformate nel corso del tempo cambiando la loro destinazione d’uso. (altro…)

Le strutture ipogee sacre sono architetture scavate nella roccia. Alcune di queste, inizialmente nate come edifici religiosi, si sono trasformate nel corso del tempo cambiando la loro destinazione d’uso. (altro…)

Durante l’Olocene il cambiamento del clima determinò condizioni favorevoli, con temperature più calde adatte alla crescita demografica. Si diffuse una flora e una fauna di tipo Mediterraneo più consona a condizioni di vita stabile. (altro…)

I complessi megalitici sono strutture preistoriche formate da grandi pietre e si trovano in tutto il mondo. Sono di diverse forme; a partire da pietre verticali isolate (menhir), a pietre verticali allineate o disposte a cerchio come nel caso di Stonehenge, Rollright Stones e Avebury in Inghilterra.

La storia delle opere idrauliche,generalmente associata alla civiltà greco-romana,ricca di grandi acquedotti,risale ad epoche molto più remote. Le tecniche dell’approvvigionamento idrico,sono state affrontate dalle più antiche culture, con sistemi, inizialmente molto semplici adeguati alle caratteristiche del territorio e dell’ambiente circostante, fino alla costruzione d’imponenti e complesse opere idrauliche.

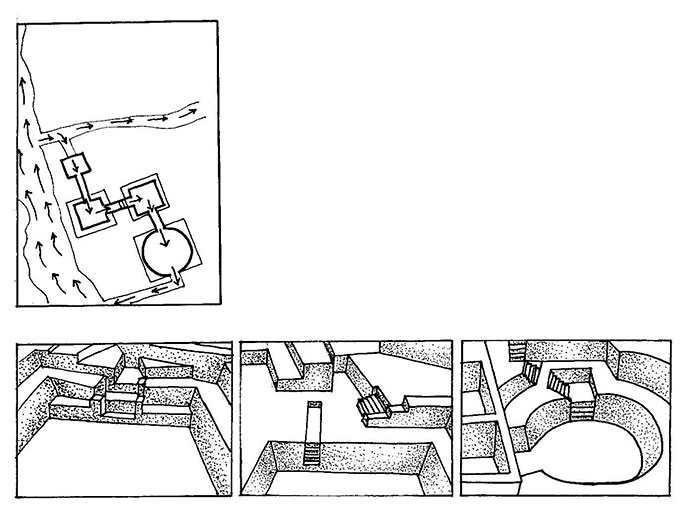

Il sistema di decantazione dell’acqua, risalente alla fine del I secolo a.C., comprendeva tre cisterne di raccolta (da percolazione) e contenimento alimentate da un canale largo undici metri e profondo cinque metri che raccoglieva le acque del Gange,dopo le inondazioni causate dai monsoni.

L’acqua,dal canale, entrava prima in una camera dove il limo veniva depositato.Quest’acqua,relativamente pulita,era poi diretta alla prima cisterna rivestita di mattoni (cisterna A) poi nella seconda cisterna (cisterna B) attraverso un’ingresso dotato di scalino ( che serviva per pulire ulteriormente l’acqua).

Questa era la cisterna primaria per la fornitura d’acqua.

Successivamente, defluiva verso una vasca circolare (cisterna C) che aveva un sistema di scalini, un elaborato contenitore di rifiuti dotato di sette canali di versamento, una cresta, ed una uscita finale che assicurava, all’acqua in eccesso, di riversarsi nuovamente nel fiume Gange.

Rappresentazione grafica delle cisterne di decantazione del sistema idraulico di Sringaverapura (India I sec. a.C.)

Il periodo Moghul ha lasciato in tutta l’India, una grande eredità in fatto di acquedotti ben progettati. Un esempio tipico, è il vecchio acquedotto di Burhanpur sulla sponda del fiume Tapti in Madhya Pradesh.

Il progetto consisteva in ”bhandaras”, cisterne di contenimento che raccoglievano l’acqua del suolo dalle sorgenti sotterranee che scorrevano dalle colline adiacenti Saptura, verso il Tapti.

L’acqua del suolo era intercettata da quattro posizioni a nord-ovest di Burhanpur e confluiva, attraverso condotti sotterranei, fino ad una camera di giunzione chiamata ”jail karanj”. Qui, era immagazzinata l’acqua per l’approvvigionamento dell’intera città.

Il sistema è oggi abbandonato,ma i suoi condotti dell’aria,vengono usati come pozzi per attingere l’acqua.

Rappresentazione grafica dell’acquedotto di Burhanpur (India)

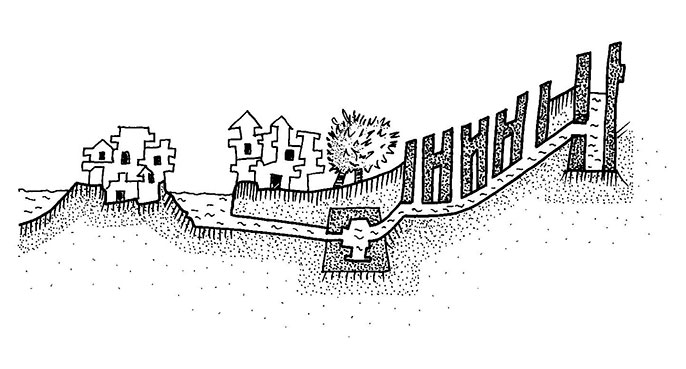

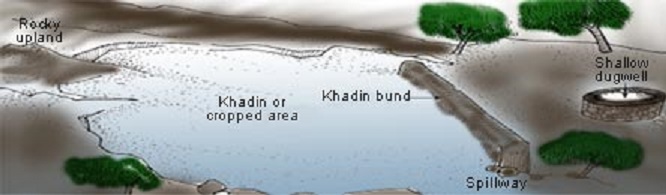

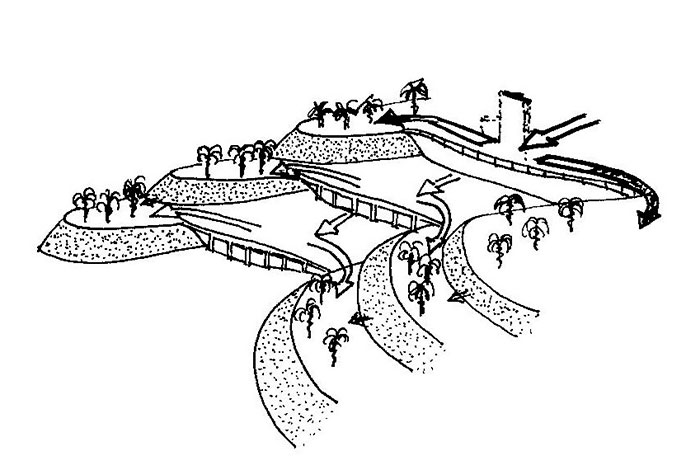

Il khadin, è un’ingegnosa costruzione progettata per raccogliere ”la fuga dell’acqua” sulla superficie e viene utilizzata nell’agricoltura. La sua principale caratteristica,è una diga di terra molto lunga costruita attraverso i pendii più bassi della collina, al di sotto degli altopiani ghiaiosi.

Chiuse e sfioratori permettono, all’eccesso di acqua,di sgocciolare. Il sistema khadin,è basato sul principio di raccolta di acqua piovana su terreni agricoli ed il successivo impiego dell’acqua, proveniente dai terreni saturi, per la produzione di colture.

Questo sistema è molto simile al metodo d’irrigazione usato nella città di Ur (Iraq) intorno al 4500 a.C., successivamente dai Nabatei nel Medio Oriente e nel deserto del Negev.

Rappresentazione grafica dell’ingegnoso sistema Khadin (India)

La civiltà dell’Indo è rinomata per le sue pratiche di gestione delle acque.

Secondo Louis Flam, l’ampia tecnologia di controllo delle acque della civiltà dell’Indo, iniziò nella regione durante il periodo Amri-Nal e si sviluppò in tre forme.

La prima è molto semplice e utilizza il naturale allagamento del ruscello collinare per irrigare i terreni ai lati del ”nai”con il minimo intervento umano.

Questa tecnica è simile a una forma di coltivazione ampiamente praticata sulle pianure alluvionali Indo conosciuta come ”sailabi”ed è stata vividamente documentata nel sito di Kahtras Buthi.

La seconda forma, documentata nel sito di Nal Bhuti, fa uso di piccoli fossati, poco profondi, per direzionare delicatamente acqua di sorgente su una zona pianeggiante che viene utilizzata per le coltivazioni.

Questo è un metodo d’irrigazione utile ed affidabile e, dal momento che le sorgenti sono attive tutto l’anno, è possibile avere un raccolto invernale di granaglie e un raccolto estivo di altre coltivazioni.

La terza forma d’irrigazione è documentata nel sito di Nuka e consiste nella formazione di un involucro protettivo o un muro di terra basso conosciuto localmente come un ”kach”o un ”gabarband”.

Qui, il terreno alluvionale è stato accumulato dietro basse dighe previste attraverso il drenaggio in pendenza, per creare una riserva d’acqua.

Un tipico esempio è il gabarband del sito di Diana sul fiume Hab, dove le acque sono state, presumibilmente, accumulate in un bacino di raccolta e rilasciate lentamente verso i campi.

Il sistema dei gabarband è originario del Belucistan e risale al periodo degli insediamenti Nal ed è ancora oggi in uso.

Fondamentalmente il Belucistan meridionale produce un raccolto di grano all’anno ed è soprattutto un ”khushkhaba” o coltura a pioggia.

La pendenza del Belucistan meridionale è, generalmente, da nord a sud tranne i suoi margini orientali dove, i flussi locali (Mula, Kulach) sfociano dentro Sindh attraverso passaggi nell’area del Kirthan.

I pricipali fiumi scorrono verso sud e passano attraverso le valli dove gli insediamenti sono più concentrati.

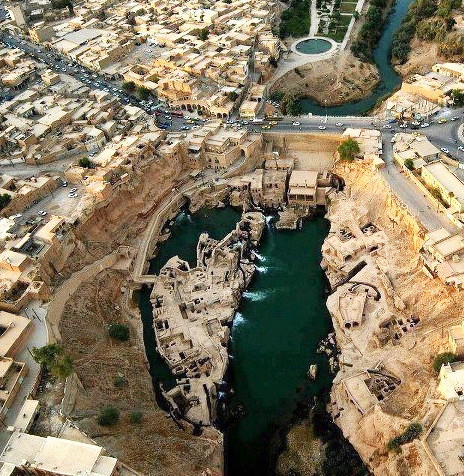

Shushtar era un’antica cittadella fortificata della Persia. Il suo sistema idrico,era un’insieme di strutture che rifornivano d’acqua la città già al tempo di Dario il Grande nel V secolo a.C. Questo sistema,era composto da due canali che estraevano l’acqua dal fiume Karun.

L’altro canale, il Gargan, ancora oggi viene utilizzato per portare l’acqua alla città. I condotti sotterranei, portano acqua ai mulini della zona. Il canale raggiunge la città da sud e fornisce d’acqua una grande zona coltivata ad orchidee.

La spettacolare cascata,cade dalla scogliera e si riversa verso le ampie zone di raccolta. Di questo complesso né fanno parte il Salasel Castle, il centro operativo del sistema idraulico, le torre di misurazione del livello dell’acqua, dighe, ponti, bacini e mulini.

Shushtar è la testimonianza dell’eredità lasciata dagli Elamiti e Mesopotami, abili maestri e dell’influenza che hanno avuto i Nabatei con la costruzione dell’ingegnoso sistena idrico di Petra.

Sistema idrico di Shushtar (Iran)

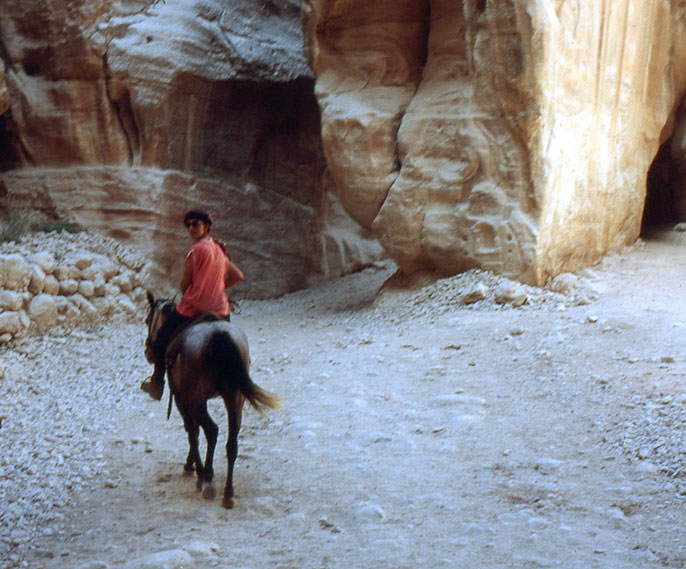

L’area archeologica della città,è una delle più estese al mondo. I gruppi locali di beduini,hanno utilizzato un sistema vecchio di 2500 anni,costruito dai Nabatei. Questo ingegnoso popolo,era riuscito a captare tutte le acque che scorrevano sulle montagne durante le scarse piogge ed a convogliarle in un articolato sistema di cisterne.

Nel tempo, le popolazioni del luogo, hanno utilizzato questo complesso sistema, continuando ad abitare le grotte, proprio grazie alla capacità di utilizzare le risorse della zona, raccogliendo e conservando l’acqua.

La profonda spaccatura chiamata siq, era il percorso delle acque del Wadi Musa che attraversava la grande città monumentale scolpita nella rosata arenaria.

I Nabatei costruirono un sistema capillare per la raccolta dell’acqua che, lungo le pareti,seminascosto tra le grandi architetture megalitiche, è ancora possibile riscontrare; una rete di ampie dimensioni composta da tubature, canali di scolo e cisterne.

Ancora oggi, dalle gole scoscese di arenaria rosa,gocciola l’acqua che viene raccolta in numerose vasche scavate nella roccia chiamate ”qottara”.

Queste cisterne, erano utilizzate dai Nabatei e dai popoli che si sono succeduti nel tempo, per il quotidiano fabbisogno di acqua.

I beduini hanno continuato ad abitare le grotte di Petra fino agli anni ’80, periodo in cui gli abitanti sono stati trasferiti per la tutela del sito archeologico.

Petra – Percorrendo il Siq a cavallo, si arriva al tempio El Kasneck

Tunnel chiamati siq, scavati dai Nabatei per deviare l’acqua, attraverso il canyon, verso l’ingresso della città

Lungo la valle dell’oued M’Zab, il corso superficiale è completamente assente.

In questa zona sorgono, tra il X e l’XI secolo,cinque città circondate da mura e affacciate sul grande palmeto che prospera grazie alla costruzione di dighe interrate che sbarrano i flussi d’acqua sotterranei.

Nasce così,un’estesa oasi con notevoli caratteristiche urbane.

La diga di Beni Isguen, conserva le acque d’inferoflusso e delle sporadiche piene dello oued M’Zab. Attinte per mezzo di pozzi,queste acque alimentano i canali d’irrigazione dei giardini.

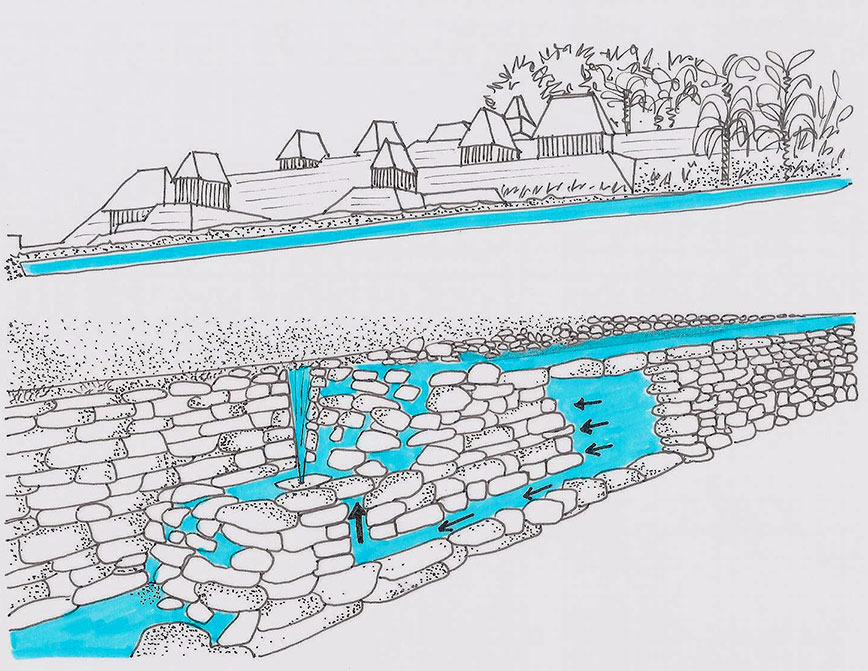

Diga di Beni Isguen (Algeria)

Le oasi dell’oued Saoura, formano un sistema lineare lungo l’alveo del fiume fossile, dai cui sedimenti traggono l’acqua con dighe che sbarrano il flusso sotterraneo. Le acque dell’Atlante, fluiscono nel grande Erg Occidentale e alimentano la falda al di sotto delle sabbie.

L’oued Saoura ha mantenuto libero il suo corso fino alla depressione del Touat.

Sbarramenti lungo il corso dell’oued, bloccano il flusso sotterraneo e permettono di drenare l’acqua dei sedimenti con canalizzazioni che irrigano i terrazzamenti ai bordi dell’alveo.

A sud del Saoura, la falda si abbassa e l’acqua viene attinta tramite grandi pozzi a bilanciere ai margini del corso del fiume fossile.

La serie dei grandi pozzi, marca il paesaggio.

Ricostruzione delle dighe di sbarramento lungo l’oued (Disegno di Natalia Tarabella modificato da disegno di Pietro Laureano)

Khottara, grande pozzo a bilanciere (Shaduf)

Diecimila anni fa, nello Yemen centrale, esisteva un sistema fluviale integrato. Gli wadi Al Jawf, Dhana, Baylan e Markha, confluivano nel wadi Hadramaut.

La vegetazione di queste valli, era da savana,molto scarsa e popolata di fauna. Nella zona ci sono molte pitture rupestri che riproducono queste figure di animali. La popolazione era di cacciatori-raccoglitori e,quindi, non era necessaria l’irrigazione dei terreni.

Nel IV millenio a.C. il clima cambiò; diventò più secco, diminuì l’acqua dei fiumi e si diradò la vegetazione.

Le popolazioni avevano bisogno di un’alternativa e cominciò, così, l’era dell’agricoltura nelle zone marginali degli wadi dove il terreno era reso più fertile dal tracimare del corso dei fiumi. Si passò, poi, alla costruzione di semplici dighe di terra per portare più acqua nei campi. Attraverso questo tipo d’irrigazione, arrivavano sedimenti freschi che fertilizzavano il terreno.

A Marib, per trattenere l’eccedenza d’acqua della piena,si costruirono piccoli muretti sulla roccia basaltica. Le sostanze trasportate dall’acqua, sedimentavano formando terra fertile per l’agricoltura. Dall’esame dei sedimenti, si può datare l’inizio dell’irrigazione a Marib nel III millenio a.C. e più a sud, forse, anche prima.

Inizialmente l’irrigazione artificiale e la costruzione di dighe, cominciò lungo gli wadi minori con semplici dighe di terra e divisori per l’acqua costruiti con pietre. Da queste semplici dighe,si sviluppò una più complessa tecnica che riusciva a convogliare anche l’acqua delle grandi piene della valle principale.

Per evitare che i campi venissero insabbiati dal vento del deserto,l’irrigazione si spostò nella zona centrale della valle,più protetta dai venti.

Si arrivò, così, al passaggio da un’irrigazione di piccola portata a quella che, in età classica, copriva grandi superfici. Intorno all’inizio del III millennio a.C. sugli altopiani dell’area di Dhamar, ci fu un cambiamento climatico che portò alla diminuzione del regime delle piogge.

Gli insediamenti umani iniziarono ad avere un’importante impatto ambientale.

La pratica dell’agricoltura si diffuse in tutti gli altopiani e la deforestazione servì per creare la costruzione di terrazzamenti a scopo agricolo. La diminuzione del manto vegetale,favorì il cambio della portata d’acqua dei fiumi che,da corsi d’acqua perenni,divennero torrenti portatori di piene stagionali. I torrenti trasportavano sedimenti che fertilizzavano il suolo,ma le piene doveveno essere controllate.

I canali scavati rinvenuti nella zona di Malayba,sono stati datati all’Età del Bronzo. La pratica dell’irrigazione era già diffusa prima che i Sabei costruissero le grandi dighe di Marib. Dall’esame dei canali è possibile pensare che esistesse un sistema vasto e misto che sfruttava sia un corso d’acqua perenne, sia le piene portatrici di sedimenti fertili.

Gli scavi testimoniano, inoltre, una diminuzione dell’ampiezza dei canali dovuta,probabilmente,alla mancanza di acqua perenne disponibile. Questo fu il motivo dell’abbandono del sistema.

Ricostruzione dell’antica oasi di Marib – Diga (H.David)

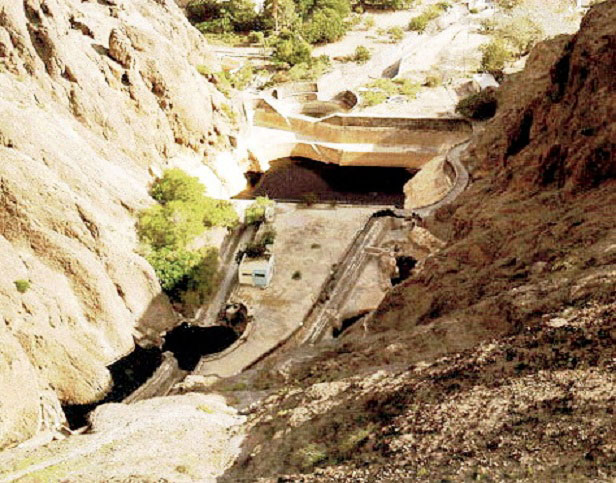

Marib – Chiusa nord della diga

Marib- Chiusa sud della diga

Acropoli di Marib

Marib – Misuratori

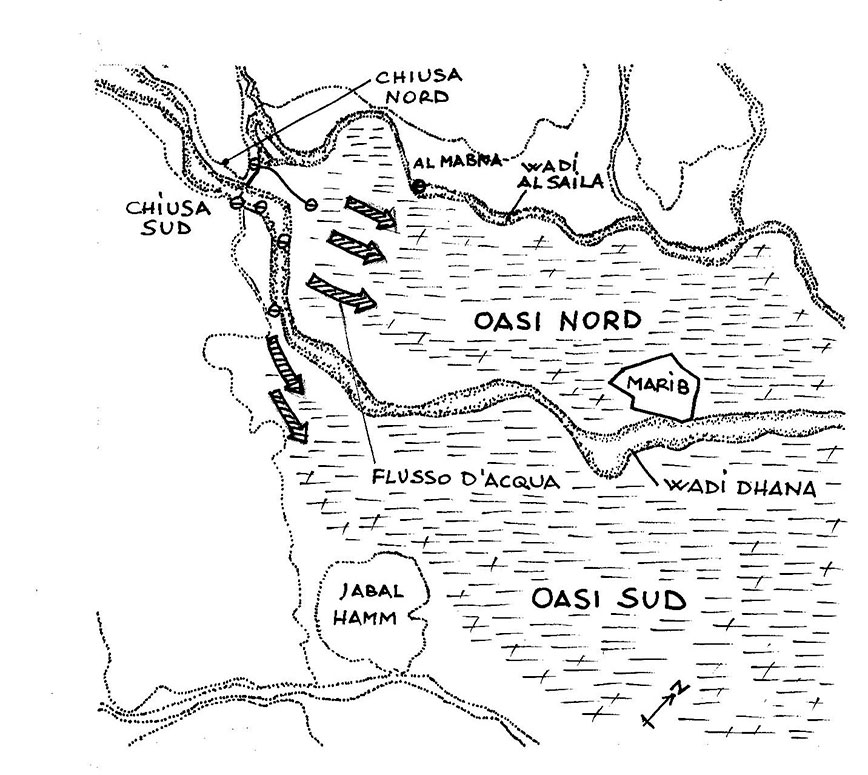

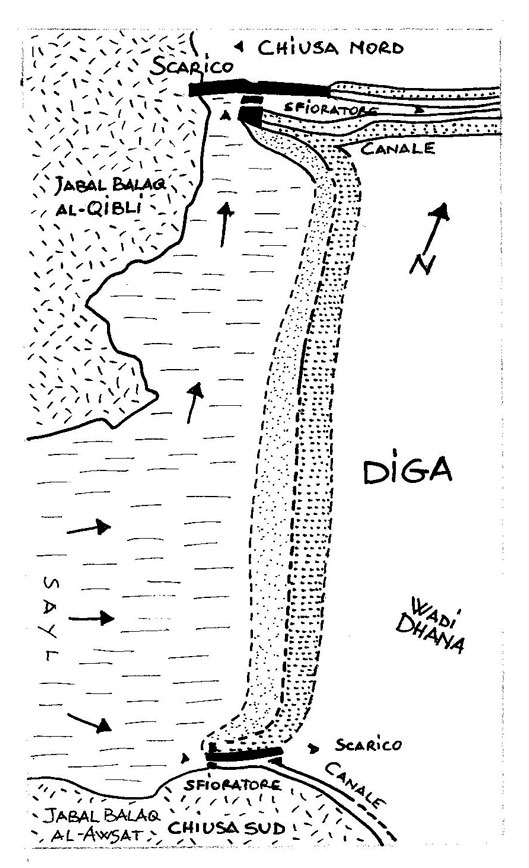

L’oasi di Marib era alimentata dal sayl del wadi Dhana. Le sue acque defluivano dall’altopiano verso il deserto. All’uscita del wadi Dhana dalla gola dei monti Balaq,la valle venne sbarrata con una diga di terra lunga 680 metri.

Questa diga serviva per innalzare l’acqua fino al livello dei campi e irrigare, così,l’intera Marib.

A sud ed a nord della diga, venne costruito,sulla roccia calcarea,un canale di scarico murato. La quantità d’acqua necessaria per alimentare il sistema dei canali, era garantita da questo sfioratore. Un canale primario portava l’acqua dalle chiuse alle zone da irrigare.Da qui,un distributore principale,alimentava il sistema di canali con le acque raccolte.I campi venivano irrigati da canali collettori in muratura,oppure tramite sfioratori in terrapieni,passando l’acqua da un campo all’altro.

L’acqua in eccesso, rientrava nello wadi situato più in basso. Le piene garantivano l’irrigazione di Marib;i campi venivano allagati e l’acqua filtrava nel limo lasciando che le sostanze fertili si depositassero. Nei periodi di siccità, le piante come le palme da dattero, venivano irrigate con l’acqua dei pozzi.

L’oasi era divisa da due giardini sui due lati del wadi Dhana. Questo metodo d’irrigazione Sabea fu mantenuto per molti secoli e la ragione della sua lunga durata,fu la semplicità del sistema e la capacità di gestire le grandi piene che si verificavano periodicamente.

Marib ed i ”due giardini” di Saba.

Dal Corano ” XXXIV la sura dei Saba – Invero la gente di Saba’ ebbero nella lor dimora un Segno : due giardini,a destra e a sinistra. Mangiate,dicemmo loro,della provvidenza del vostro Signore e rendeteGli grazie; una buona terra avete e un Signore indulgente”.

Ricostruzione del particolare delle due chiuse della diga di Marib (U.Brunner)

Le cisterne preislamiche di Aden, chiamate della regina di Saba, servivano per l’approvvigionamento idrico e per proteggere, dall’acqua alta,l’antica città portuale di Aden situata allo sbocco del cratere vulcanico.

L’acqua raccolta nel cono vulcanico,era immagazzinata in una serie di profonde cisterne. In passato, il cratere, era impermeabilizzato e funzionava come un’ampio dispositivo di captazione dell’umidità che alimentava le vasche di raccolta.

Le cisterne di Aden collocate sul cratere del vulcano

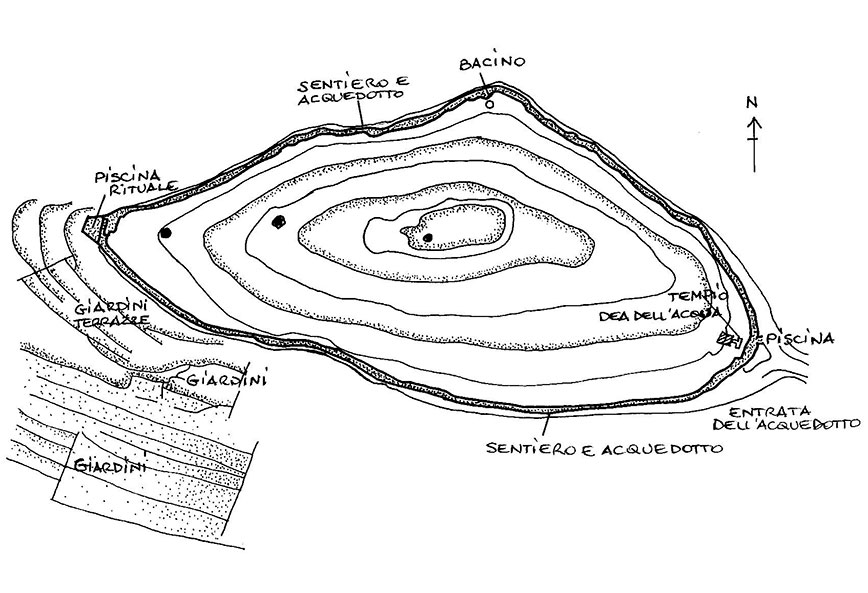

Situata sulle pendici del monte Tlaloc, a est di Tetzcoco, questa collina è un grande sito archeologico circondato da terreni agricoli a terrazze. E’ uno straordinario luogo per i riti della pioggia dato che questi monti,grazie alle loro sorgenti e alle nuvole cariche di pioggia che si addensano intorno alle loro vette,sono le fonti d’acqua primarie per l’Acolhuacan centrale.

Tetzcotzingo e il monte Tlaloc svelano il ruolo religioso essenziale dei sovrani aztechi in quanto responsabili della caduta della pioggia e del passaggio dalla stagione secca a quella umida. Nel recinto sacro,sopra la foresta, i sovrani entravano nel luogo di contatto tra cielo e terra, facevano delle offerte e tornavano a casa come portatori dell’acqua, donatrice di vita.

I templi sacri, sono racchiusi dal sentiero che corre parallelo all’acquedotto e nel sito sono presenti piscine rituali e un bacino.

Ricostruzione della zona sacra atzeca sulla collina di Tetzocotzinco

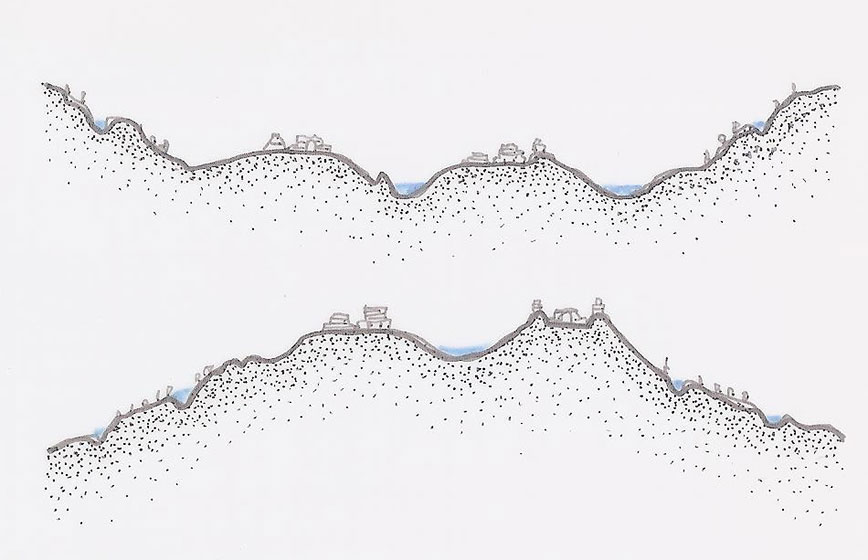

A) Nel periodo preclassico gli insediamenti sono realizzati a valle dentro depressioni naturali utilizzate come riserve d’acqua.

B) Nel tardo periodo classico, la tecnologia idraulica permette di costruire nei luoghi elevati utilizzando la città con i suoi tetti e monumenti come captatori di acqua che alimentano una grande riserva centrale.

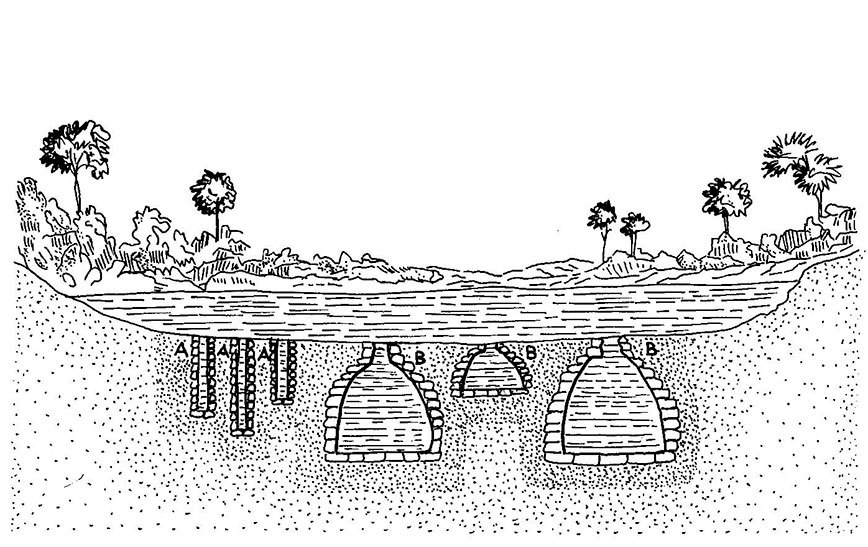

Ricostruzione della tecnologia idraulica Maya A) Periodo pre classico – B) Tardo periodo classico

E’ una struttura idraulica scavata nella città Maya di Palenque (acquedotto di Piedras Bolos). E’ lunga circa sessanta metri ed ha una pendenza di sei metri.

L’acqua scorre lungo la rampa e finisce contro una barriera dove,costretta a passare attraverso un tubo molto stretto,produce un’alta pressione.

Ricostruzione della struttura idraulica di Palenque

Sistema Maya per incanalare l’acqua pluviale raccolta dalle coperture degli edifici, dalle piazze e dalle vie della città.

Utilizzando la forza di gravità, l’acqua scorre e attraverso delle canalizzazioni, finisce in depositi situati nella zona.

Con i pozzi (A) ed i chultun (B) si conserva l’acqua quando l’aguada (C) diviene secca.

Ricostruzione dell’Aguada Maya A) Pozzi – B) Chultun – C) Aguada

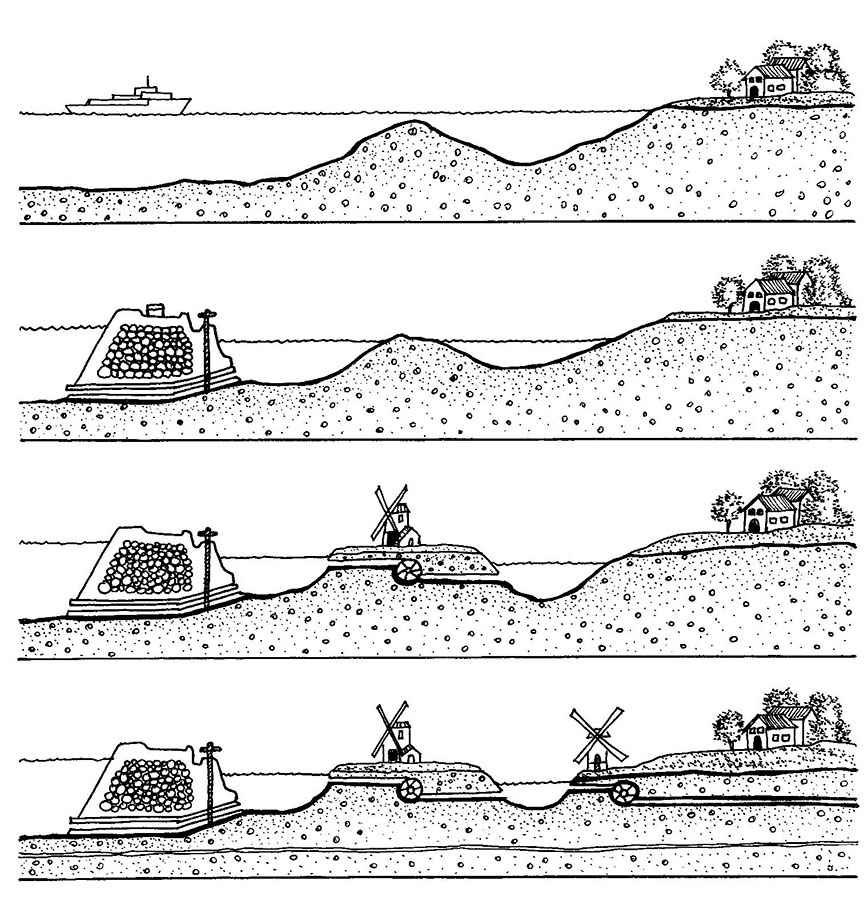

Il territorio olandese è,per la maggior parte,situato al di sotto del livello del mare. Il polder è una zona prosciugata artificialmente mediante dighe e sistemi di drenaggio dell’acqua.

Gli abitanti avevano bisogno di terra per l’agricoltura e per i pascoli e già dal medioevo, vennero adottate queste tecniche idrauliche. Nel XVII secolo,venne perfezionata la tecnica per prosciugare i tratti di mare con l’introduzione di mulini a vento che sfruttavano la forza del vento per catturare l’acqua ed espellere, in mare, quella che rimaneva dentro le dighe.

Ricostruzione del sistema Polder (Paesi Bassi)